Language carries history

Introduction

To demonstrate language carries history, I'll use Unicode.

Unicode

First, what “Unicode”? Unicode defines encoding characters (formally, graphemes, a minimally distinctive unit of writing), including letters, symbols, and emoji 😮. Unicode covers most of the world's writing systems, and nearly all web pages use Unicode (UTF-8).

Unicode provides a unique code point, a number, for each character. For example, the (decimal) number 75, 0b01001011 in binary, represents the uppercase K. Computers represent data in binary, so essentially Unicode provides a mapping from binary data to characters.

Han ideographs

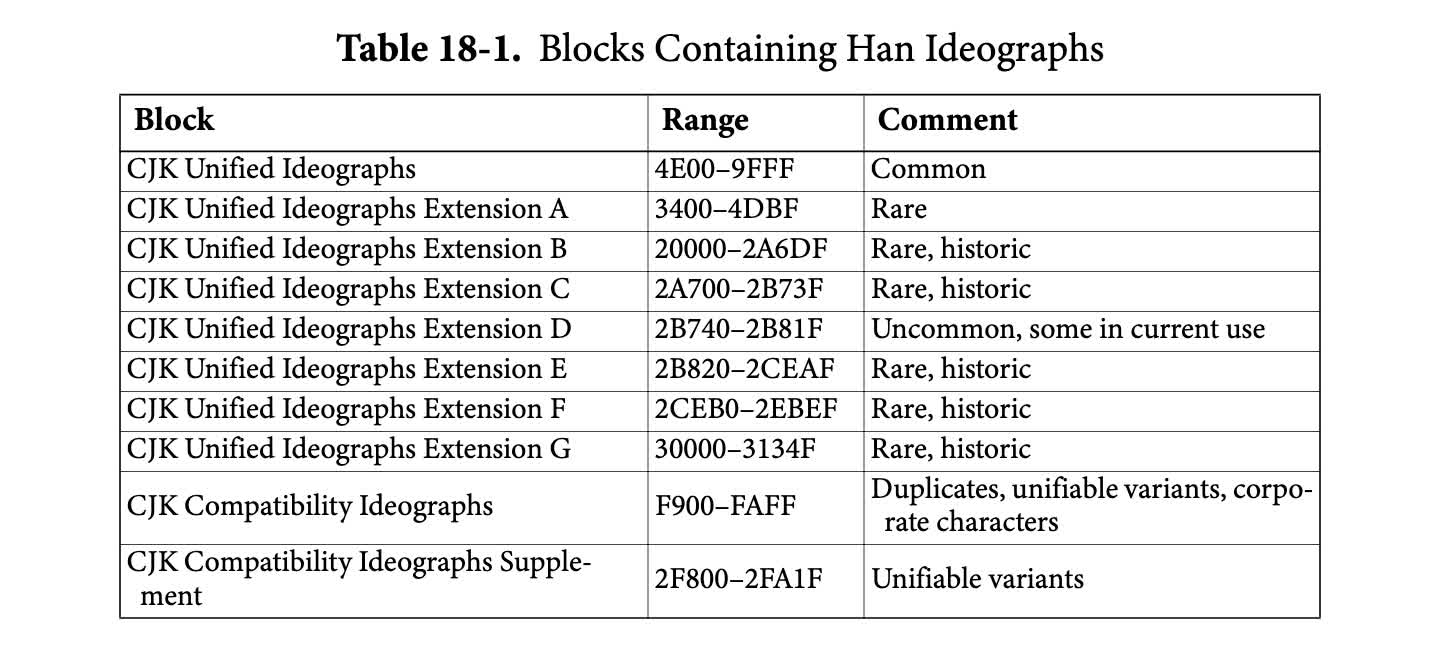

Those of us who read and write in English work with 26 letters. However, reading and writing in Mandarin involves thousands of characters. The 汉语大字典 counts over 50,000. However, you only need to know 2,600 to pass the 汉语水平考试 (the HSK), and less than 1,000 to function in everyday life. Unicode provides code points for all of these:

For example, hexadecimal 0x4E2D, binary 0b0100111000101101 and decimal 20013, represents 中.

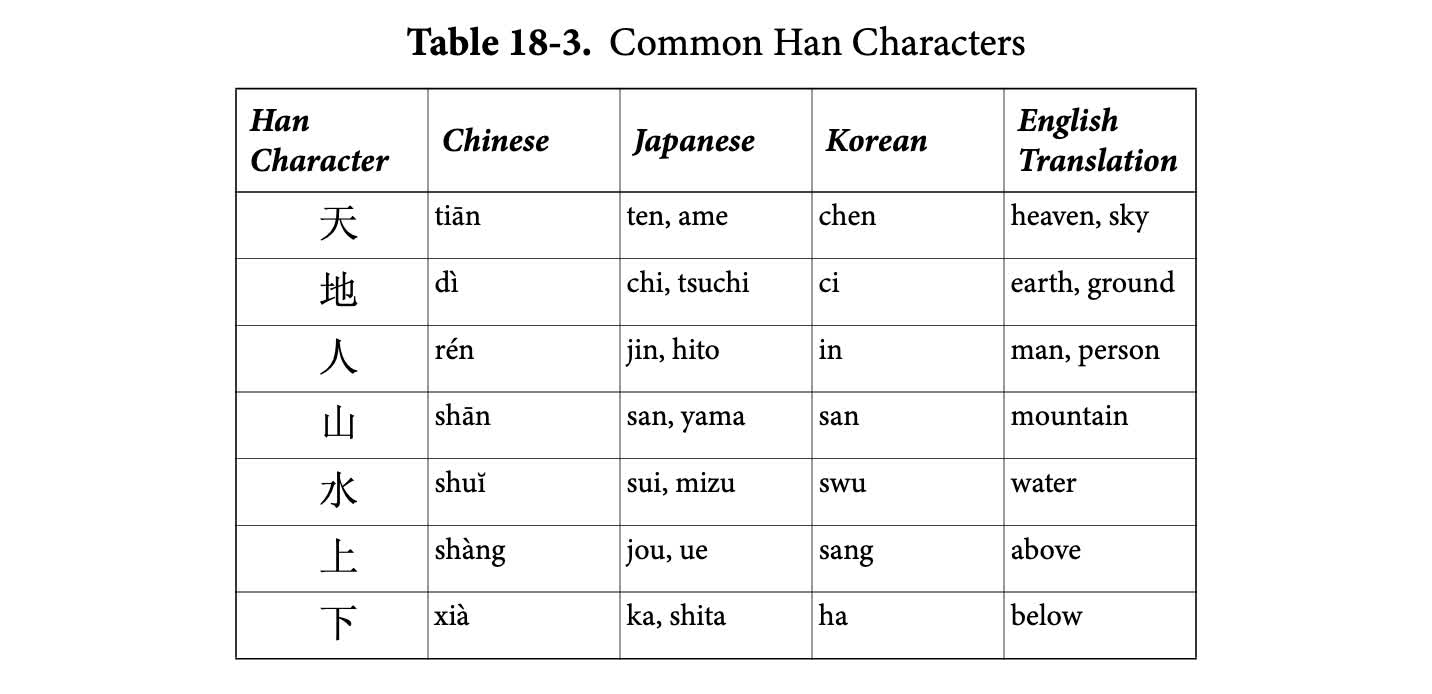

Wait, what do we mean “Han ideographs”? We basically mean Chinese characters. Han, derived from the Chinese Han Dynasty, refers to the largest ethnic(/cultural) group in China, making up over 90% of the population. Han characters appear throughout Chinese, Japanese, and Korean text. As Unicode states:

The influence of the Chinese language and its written form on the modern East Asian languages is … immediately visible in the mixture of Han characters and native phonetic scripts … now used in the orthographies of Japan and Korea

Modern Japanese text mixes 仮名 (平仮名 and 片仮名) with 漢字 (Han characters). 平仮名, Unicode code points U+3040 to U+309F, and 片仮名, Unicode code points U+30A0 to U+30FF, descend from 万葉仮名, which used Han characters to represent the Japanese language phonetically. Interestingly, in Japanese, you would pronounce 漢字 as kanji, referring to using Han characters in Japanese text. The traditional Chinese writing system uses those same characters to refer to itself. So in Chinese, you would pronounce 漢字 as hànzì, referring to using Han characters in Chinese text.

Meanwhile, though older traditional Korean literary materials prominently use Han characters, modern Korean text consists almost entirely of 한글, syllables spanning Unicode code points U+AC00 to U+D7A3. In the 15th century, 세종대왕 created 한글 to promote literacy through simplicity. The modern 한글 alphabet consists of 24 basic letters: 14 consonants and 10 vowels, much fewer than the tens of thousands of Han characters. Elites and scholars, especially Korean Confucian scholars, opposed 한글, preferring Han characters.1 Thus, 한글 did not see widespread official use until the 20th century. During Japanese occupation of Korea, Koreans, particularly the 한글 학회 standardized 한글 and kept it alive. Then in 1946, with the fall of Imperial Japan, 한글 gained official status, largely replacing Han characters in modern Korean text.

Conclusion

As I've demonstrated, language, even down to the character level, carries history. I hope this inspires curiosity in the letters and characters of other languages.

This writing system using Han characters for Korean text, pronounced hanja, also uses the characters 漢字 to refer to itself. ↩︎